by: Dominic Bush

August 7, 2015

As we make our way back to hot showers, flushable toilets, and sales tax, I want to give as accurate of a picture possible of our time in the Philippines. So, without further adieu, I present 101 Things I (We) Did In Field School:

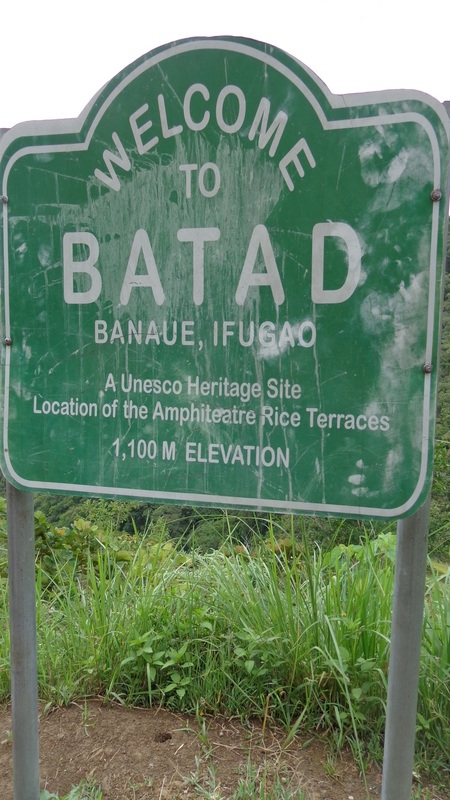

101. Met a group of strangers in the airport. 99. Flew across the Pacific Ocean. 98. Ate a first meal consisting of fries, fried chicken, and mango-peach pies. 97. Tried balut. 96. Went to the craziest, most insane mall ever imagined. 95. Traveled through Manila traffic. 94. Rode on a freezing bus for 9 hours on the way to Ifugao. 93. Washed dishes outside, sometimes without light, in basins. 92. Rewashed dishes because they were not up to certain standards. 91. Swept the house floors with all the bugs on it. 90. Flushed a toilet with a bucket and threw the toilet paper in a trash can. 89. Emptied said trashcans. 88. Bathed using a bucket, a scoop (tabo), and freezing water. 87. Filled drums with freezing water in anticipation of water running out. 86. Learned to use a compass. 85. Rode in/on the back of a tric. 84. Woke up to a spider, moth, ant etc. on me. 83. Was personally victimized by a giant, flying beetle. 82. Learned how many steps it took me to cover 10 meters and never used this information. 81. Saw the largest spider of my life. 80. Rode Big Blue, our favorite, somewhat reliable jeepney. 79. Crossed a river to get to the site by carefully balancing on rocks. 78. Crossed through the river after not caring anymore. 77. Excavated using a trowel, shovel, pick ax, and piece of rebar. 76. Drank rehydration salts. 75. Talked to a carabao (water buffalo). 74. Bailed out water after trenches flooded. 73. Dug barefoot because the mud made shoes impractical. 72. Mapped a unit. 71. Got excited about finding my first pot sherd. 70. Got considerably less excited after finding my 500th pot sherd. 69. Made a joke anytime a measurement was 69. 68. ACCESSIONED. 67. Got mad when small sherds were individually accessioned. 66. Potwashed, which doubled as very necessary therapy sessions. 65. Carefully excavated around faunal remains, only to break them when pulling them out. 64. Screened. 63. Wet screened. 62. Gave up on screening and resorted to hand sifting. 61. Got overly excited when burgers, donuts, or ice cream were brought to the field. 60. Washed my hands in irrigated water before lunch. 59. Prayed for rain after lunch. 58. Struggled to set up shade tents, gave up, and asked SITMo boys to do it. 57. Learned plastic green rope can fix anything. 56. Ate pig ears and fish heads. 55. Argued with a supervisor. 54. Roasted a pig. 53. Used said pig’s bones to help identify faunal remains. 52. Drank a liter of Royal (orange soda)…or like 15. 51. Became envious of all those who received haircuts from Ate Marlon. 50. Had the best fried chicken of my life at Saturday Market. 49. Went to church…lol. 48. Hiked to a waterfall. 47. Stayed in a traditional Ifugao house. 46. Struggled to sleep in a traditional Ifugao house because of the bugs that were also staying there. 45. Followed Doc through a “shortcut” on the way out of the Batad terraces. 44. Almost collapsed during/after hike out of Batad. 43. Played an impromptu game of twister in the jeepney ride home from Batad. 42. Agreed to go to the Rice Festival, I mean Rice Ritual. 41. Hiked to the ritual in flip-flops (Okay I didn’t but it was a treat watching the rest do so). 40. Witnessed a pig sacrifice. 39. Drank rice wine. 38. Engaged in and arguably won a splash war with the local kids at the pool in Kiangan. 37. Bought pineapple out of the back of a truck. 36. Sang videoke. 35. Ate meat on a stick. 34. Rode on a bus for 8 hours to the beach. 33. Met Dr. Ting, and I’ll leave it at that. 32. Played Never Have I Ever, and learned a lot about the other members of IAP. 31. Was never more excited for McDonald’s. 30. Laughed at the thought of turning in a research paper. 29. Came to love Yanna (the dog) despite her fleas, mange, stench, and destructiveness. 28. Listened to A LOT of Taylor Swift. 27. Reconstructed Pots. 26. Learned about Guam courtesy of Mariana. 25. Opened bottles with a spoon. 24. Became a large financial supporter of Ate Pauline’s sari-sari (variety) store. 23. Fried my computer, Megan also knows the pain. 22. Thoroughly enjoyed whenever any IAP member dressed up in traditional Ifugao clothes, especially the G-string. 21. Celebrated two member’s birthdays. 20. Had my future read through tarot cards. 19. Watched and participated in a traditional Ifugao dance ceremony. 18. Flotation. 17. 1738. 16. Became very familiar with Justin Bieber’s “Where Are U Now,” and Demi Lovato’s “Cool for the Summer.” 15. Made sure I knew where my tupperwear was at all times. 14. Owed my life to SITMo on numerous occasions. 13. Wiped all my documents on my USB and threw a chair; Rico taught me that outlet. 12. Stressed out about writing research paper. Bought and ate an entire box of Choco Mucho candy bars. 11. Fell in love with squash balls and siopao (meat bun). 10. Emperador, Ginebra, and San Miguel. 9. Enjoyed some of the best food of my life thanks to Uncle Johnny. 8. Wrote a research paper. 7. Attempted to break curfew, just so I could sit downstairs and talk to other IAP members for an extra 15 minutes. 6. Presented at the National Museum. 5. Went to the Imperial Ice Bar. 4. Felt strange taking hot showers and flushing toilets at the hotel in Manila. 3. Choked up saying goodbyes. 2. Did not recognize the Manila airport the second time around. 1. Made friends for life and memories I’ll never forget.

So even if there’s not a next time, I will always remember that time I spent my summer in the Philippines with 20 something strangers digging holes in mud as one of the best experiences of my life. Signing out.

August 7, 2015

As we make our way back to hot showers, flushable toilets, and sales tax, I want to give as accurate of a picture possible of our time in the Philippines. So, without further adieu, I present 101 Things I (We) Did In Field School:

101. Met a group of strangers in the airport. 99. Flew across the Pacific Ocean. 98. Ate a first meal consisting of fries, fried chicken, and mango-peach pies. 97. Tried balut. 96. Went to the craziest, most insane mall ever imagined. 95. Traveled through Manila traffic. 94. Rode on a freezing bus for 9 hours on the way to Ifugao. 93. Washed dishes outside, sometimes without light, in basins. 92. Rewashed dishes because they were not up to certain standards. 91. Swept the house floors with all the bugs on it. 90. Flushed a toilet with a bucket and threw the toilet paper in a trash can. 89. Emptied said trashcans. 88. Bathed using a bucket, a scoop (tabo), and freezing water. 87. Filled drums with freezing water in anticipation of water running out. 86. Learned to use a compass. 85. Rode in/on the back of a tric. 84. Woke up to a spider, moth, ant etc. on me. 83. Was personally victimized by a giant, flying beetle. 82. Learned how many steps it took me to cover 10 meters and never used this information. 81. Saw the largest spider of my life. 80. Rode Big Blue, our favorite, somewhat reliable jeepney. 79. Crossed a river to get to the site by carefully balancing on rocks. 78. Crossed through the river after not caring anymore. 77. Excavated using a trowel, shovel, pick ax, and piece of rebar. 76. Drank rehydration salts. 75. Talked to a carabao (water buffalo). 74. Bailed out water after trenches flooded. 73. Dug barefoot because the mud made shoes impractical. 72. Mapped a unit. 71. Got excited about finding my first pot sherd. 70. Got considerably less excited after finding my 500th pot sherd. 69. Made a joke anytime a measurement was 69. 68. ACCESSIONED. 67. Got mad when small sherds were individually accessioned. 66. Potwashed, which doubled as very necessary therapy sessions. 65. Carefully excavated around faunal remains, only to break them when pulling them out. 64. Screened. 63. Wet screened. 62. Gave up on screening and resorted to hand sifting. 61. Got overly excited when burgers, donuts, or ice cream were brought to the field. 60. Washed my hands in irrigated water before lunch. 59. Prayed for rain after lunch. 58. Struggled to set up shade tents, gave up, and asked SITMo boys to do it. 57. Learned plastic green rope can fix anything. 56. Ate pig ears and fish heads. 55. Argued with a supervisor. 54. Roasted a pig. 53. Used said pig’s bones to help identify faunal remains. 52. Drank a liter of Royal (orange soda)…or like 15. 51. Became envious of all those who received haircuts from Ate Marlon. 50. Had the best fried chicken of my life at Saturday Market. 49. Went to church…lol. 48. Hiked to a waterfall. 47. Stayed in a traditional Ifugao house. 46. Struggled to sleep in a traditional Ifugao house because of the bugs that were also staying there. 45. Followed Doc through a “shortcut” on the way out of the Batad terraces. 44. Almost collapsed during/after hike out of Batad. 43. Played an impromptu game of twister in the jeepney ride home from Batad. 42. Agreed to go to the Rice Festival, I mean Rice Ritual. 41. Hiked to the ritual in flip-flops (Okay I didn’t but it was a treat watching the rest do so). 40. Witnessed a pig sacrifice. 39. Drank rice wine. 38. Engaged in and arguably won a splash war with the local kids at the pool in Kiangan. 37. Bought pineapple out of the back of a truck. 36. Sang videoke. 35. Ate meat on a stick. 34. Rode on a bus for 8 hours to the beach. 33. Met Dr. Ting, and I’ll leave it at that. 32. Played Never Have I Ever, and learned a lot about the other members of IAP. 31. Was never more excited for McDonald’s. 30. Laughed at the thought of turning in a research paper. 29. Came to love Yanna (the dog) despite her fleas, mange, stench, and destructiveness. 28. Listened to A LOT of Taylor Swift. 27. Reconstructed Pots. 26. Learned about Guam courtesy of Mariana. 25. Opened bottles with a spoon. 24. Became a large financial supporter of Ate Pauline’s sari-sari (variety) store. 23. Fried my computer, Megan also knows the pain. 22. Thoroughly enjoyed whenever any IAP member dressed up in traditional Ifugao clothes, especially the G-string. 21. Celebrated two member’s birthdays. 20. Had my future read through tarot cards. 19. Watched and participated in a traditional Ifugao dance ceremony. 18. Flotation. 17. 1738. 16. Became very familiar with Justin Bieber’s “Where Are U Now,” and Demi Lovato’s “Cool for the Summer.” 15. Made sure I knew where my tupperwear was at all times. 14. Owed my life to SITMo on numerous occasions. 13. Wiped all my documents on my USB and threw a chair; Rico taught me that outlet. 12. Stressed out about writing research paper. Bought and ate an entire box of Choco Mucho candy bars. 11. Fell in love with squash balls and siopao (meat bun). 10. Emperador, Ginebra, and San Miguel. 9. Enjoyed some of the best food of my life thanks to Uncle Johnny. 8. Wrote a research paper. 7. Attempted to break curfew, just so I could sit downstairs and talk to other IAP members for an extra 15 minutes. 6. Presented at the National Museum. 5. Went to the Imperial Ice Bar. 4. Felt strange taking hot showers and flushing toilets at the hotel in Manila. 3. Choked up saying goodbyes. 2. Did not recognize the Manila airport the second time around. 1. Made friends for life and memories I’ll never forget.

So even if there’s not a next time, I will always remember that time I spent my summer in the Philippines with 20 something strangers digging holes in mud as one of the best experiences of my life. Signing out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed